Innovation as renewal: how kaupapa guides us - Te Taumata Toi-a-Iwi

Innovation as renewal: how kaupapa guides us

This is the second article in a series: The Future Emerging: Innovation in Arts and Culture in Aotearoa. You can start the series here.

Not all innovation has equal value. Novel practice can spark imagination. It can inspire and break barriers. Equally, innovation can also be boring, but highly effective. If we shift how we organise ourselves – policy and governance – it could lead to significant transformation – the so called ‘boring revolution’[1] . Sometimes the value of innovation is not the discernible impact of an isolated project, but the skills and capacity that grows through the process of experimentation and paves the way for more meaningful action later.

“A spark from a small vanguard of courageous people can light up a new pathway”[2]

– Attributed to Jane Marsden by Chellie Spiller

The value and importance lie not in the novelty of an idea but in what transformation is possible. What is the purpose and mission that moves us to action? Who needs to be involved, and what impact will this have if it’s successful? This can be viewed in several ways:

Purpose: Motives for innovation range from the functional (such as organisational productivity or income diversification), to the strategic (such as new collaborations or partnerships), to the purely exploratory and inspirational. Clarity and shared understanding are important.

Spatial: What is the scale of the transformation possible? How far will the ripple effects spread? Will it transform the creatives involved, the artform more broadly, the organisation, or the local or regional context? Will it change the very conditions in which arts and culture thrives in Aotearoa?[3] What action do we need to take now to make that ambition possible?

Temporal: How lasting will the effect be? Beyond projects and events, how will the people, organisations, culture, and landscape be changed over time? Will it have a lasting impact and will the change be sustained? The environment of arts and culture in Aotearoa has evolved to incentivise and limit us to short-term projects. How might our relationship to our work change if we think intergenerationally? How would our understanding of the process and purpose of innovation change?

New, from where we stand

Innovation is the word of the moment, but neither the word nor concept is new. It dates to sixteenth century England and originally meant change and renewal. Later, it was adopted by economists to mean the introduction of new products and process as the basis for competition. The original meaning is more aligned with Te Ao Māori. In this interpretation ‘newness’ considers what has gone before, and what could change for the future.

One of the richest sources of innovation is unlikely new combinations, interpretations or applications of existing knowledge – part of the continual change and renewal within culture and organisations.

For example, Foundation North’s Gulf Innovation Fund (G.I.F.T) invites ideas that use traditional knowledge in new ways, a value of Mātauranga Māori alongside Western Science, to restore the mauri of Tīkapa Moana and Te Moananui ā Toi.

An idea, or a pathway to something new?

Much of the talk and activity in innovation concentrates on the ‘idea’ or project and seeks novelty and quick results. But there is a lot of invisible work that happens before a quality idea emerges. People need time to observe how things work, and how they don’t. Innovative teams are motivated through a shared frustration about how things are and co-create a vision for how they could be. Innovators embark on research and conversations to explore emergent ideas. They commit their creative energy. They ruminate, critique, and improve.

Innovators also build new bridges within and between sectors. They can bring in new collaborators that align around a purpose. They can create unlikely combinations and uncover possibilities.

All of this is unseen work. Most of it is unfunded. It is often rushed.

The generation of quality ideas rarely happens in the linear and time-pressured process of grant proposal writing.

There are innovation teams that spend a large proportion of their time in this space, exploring problems, co-designing ideas and possible solutions, and carrying out early tests to eliminate ideas without merit.

To judge the idea in isolation misses the talent, time, process, and care that is needed to generate good ideas. This can also disadvantage teams that can’t make this investment because time was tight, resource short, and just surviving doesn’t leave overhead for higher level thinking, and unfunded action.

A note to funders:

Consider funding the exploration phase for people that have shown talent for innovating in the past or show characteristics that indicate they can innovate in the future. Rather than funding discrete ideas, invest in people to embark on an innovation journey; to establish the Kaupapa for the work; and to build deep collaborative relationships. This kind of investment can create strong foundations for sustained innovation. This may be part of a participatory activity with others, or self-directed by creatives who then explore potential partnerships and relationships on their own terms. Careful consideration for creative autonomy and IP protection is needed.

Moon shots and puddle jumps

Innovation varies by scale and ambition. Is it a moon shot or a puddle jump?[4]

Moon shots are radical, bold moves that can be high-risk and hold the potential for transformational impact if they are successful. The aim is nothing less than to create something that has not existed before, something that takes us closer to a desired imagined future. It is transformational.

Puddle jumps are incremental advances that can support and strengthen the arts and culture sector in Aotearoa. They are about optimising, improving, and evolving current practice.

Whether the proposed innovation is a moon shot or a puddle jump may not impact on the scale of the first phase of experimentation. Not all transformational innovation is big and expensive and results in a grand success or failure. Small experiments are possible, even when the aim is transformation. The most challenging part is to design an experiment that will give a meaningful indication about whether it could be feasible (it can be done), desirable (people want it), and viable (it can be commercial or funded) at the scale that is intended.

The birds-eye-view of a funder

When funders invite applications for innovation in arts and culture they get a bird-eye-view of the landscape. This is a view not available to many. If people are submitting bids for similar incremental innovations, but view them as radical, it indicates fragmentation across the sector; that connections, communication and learning needs to be enhanced. The funder can then play a part here in recognising patterns, sharing an overview, and making direct connections between people that are innovating in the same space. This should come with incentives to collaborate or share learning in a way that respects and protects artistic IP.

This is particularly important to consider when inviting proposals for innovation from across the country. Networks in urban centres may have greater exposure to national and international innovation than their regional counterparts, simply because of the density of activity, frequency of exposure to others’ work, and geography.

It’s vital that funders don’t perpetuate inequity by considering ‘newness’ only at the national scale. To mitigate this, they should consider taking a role in facilitating or funding bridges between urban centres and regional clusters to ensure that next practice and innovation spreads throughout Aotearoa.

The unlikely suspects

Moon shots are not the reserve of larger organisations with the capacity and resources to take bigger risks or attract well-resourced partners. There is some evidence that larger organisations actually programme fewer innovative works than smaller ones. In more normal times these larger organisations have the advantage of stability and resource, while smaller organisations can have greater agility and experience less inertia.[5] However, the disruption caused by COVID-19 has shown that arts and culture organisations experience vulnerabilities, no matter the size of the organisation.

Often innovation that disrupts the status quo comes from people and places at the edges. Places where established practice, values, and models are not so ingrained. At the edges, networks extend beyond the usual suspects. Connection and co-creation are possible with people that have diverse experiences, talents, and knowledge. Entirely new ideas can come from unexpected combinations of people and ideas.

Plans are a best guess

Once one or more ideas have been identified a lot of work goes into experimenting, learning and iterating to evolve an idea from the original proposal into a workable effective new innovation. An idea is nothing without implementation.

This journey can take people to a radically different place from where they started. It’s an exciting, uncomfortable, and necessary process to see if an idea has merit. If an idea doesn’t evolve during implementation it could indicate that the idea wasn’t especially radical: the path was clear, the assumptions were all correct. Or it could be the team didn’t sense and respond to the incremental learning that comes with experimentation. It can be tempting to faithfully execute a plan instead of learning from iteration in that messy way that is inherent in the innovation process.

Risk or potential?

Trying new things is inherently risky. The role of administrators, leaders, and managers is to accept risk without killing creativity. This requires a strong Kaupapa, commitment of resource, and the freedom to execute, experiment and adapt. It’s also possible to take a portfolio approach which include incremental innovation projects alongside bigger endeavours.

The likelihood of success isn’t solely about ambition or risk in a project, but about how many enabling factors are in place. How well placed are this group of people, at this time, to make this happen?

It’s also important to consider the transformation that is possible if the project is successful. A focus on potential, with an informed optimism, presents a better chance of success than a focus on risk of failure and potential downsides. A focus on risk alone will limit potential before it’s even begun. It’s also worth considering the alternative, what’s the risk if we don’t innovate?

There is also potential in ‘productive failure’. This is failure that provides sufficient learning to move the endeavour closer to achieving the outcomes. It does not maximise performance in the short-term but maximises learning in the long-term.

Adapt, rather than adopt, innovation methods

NESTA has supported R&D in the Arts to enable early-stage prototyping with some success. Through experimentation they also discovered that some commercial models of innovation support cannot be simply transferred to the arts and culture sector.[6] Practices, such as dragon’s den pitching and accelerator programmes, are designed for the context and values of the commercial world. Competition; a paternalistic relationship with investors; and economic potential as priority, are all inherent in these models. Careful consideration needs to be given to how well these practices serve an arts and culture Kaupapa and how they can be adapted to reflect and promote these values – taking and adapting only those practices that work within the context.

How do we understand ‘performance’?

Measuring success in innovation in arts and culture is more than the metrics of audience members, income generation and alternative income streams. These metrics can be reassuring but can offer a false sense of simplicity as the reality is complex. Many traditional evaluation methods, including most performance measurements, inhibit rather than support actual innovation.[7]

Chellie Spiller sees “a pervasive need to reassure ourselves that we are on track – that if we knock off those KPIs and indicators and stick with the plan, on-time and on-budget, that we are on track for meeting our goal.” She challenges this singular focus on certainty, and whether it is really dealing with reality. Innovation is messy, hard to navigate, and will often require a change of direction.

This requires us to ‘embrace the unknown’, ‘find opportunity in adversity’, to tune in and make sense of the complexity rather than to ignore it. Numbers can tell us very little about the journey, how well we navigated, and whether the Kaupapa was fulfilled.

A core capacity in innovation is evaluating ideas and learning by doing. That includes sensing and making sense of what is happening and its ripple effects. This is used to understand and adjust direction in real-time. The innovation process and the evaluation merge.

Chantelle Whaiapu illustrates this beautifully with the story of navigators on the sea that took time to lie down in the hull of the waka to listen to the sound of the water as it lapped the sides. The sounds gave them signals about the direction of the waka, and they used their knowledge to maintain or to adjust their direction.

There should be a Focus on Learning and the Degree of Innovation, rather than ‘Successes’. Evaluations of innovative projects and programmes should identify the extent to which there has been any attempt to learn from ‘failures’ (as well as from ‘successes’); to identify implications for the future; and the extent to which action has been taken based upon what has been learned.

A note about time

Major innovations rarely can be developed or properly assessed in the short term. Certainly three months or twelve months (the most common timeframe) is much too soon to evaluate the impact of most innovative activities.

For example, frequently there is a tendency to evaluate the impact of pilot or demonstration projects before they have had a chance to get established and to work through the inevitable problems. Iteration is needed to learn and develop any initiative. Iteration is the repetition of the ‘design – build – test’ process to generate a ‘better’ solution. Each iteration should bring the team closer to the desired outcome. For example, digital products are rarely finished but are continuously developed.

Evaluation of NESTA’s work in the UK funding and supporting R&D and the Arts has shown that, while it was relatively easy to see the immediate impact of funding on the activities by grant recipients, the outcomes are not likely to happen in the short-term.[8] It can take ‘significant time’ for prototypes to be generated or new products, processes or service introduced to the market. Changes in the organisation, innovation culture and behaviour, and the sustainability of initiatives will take even more time.

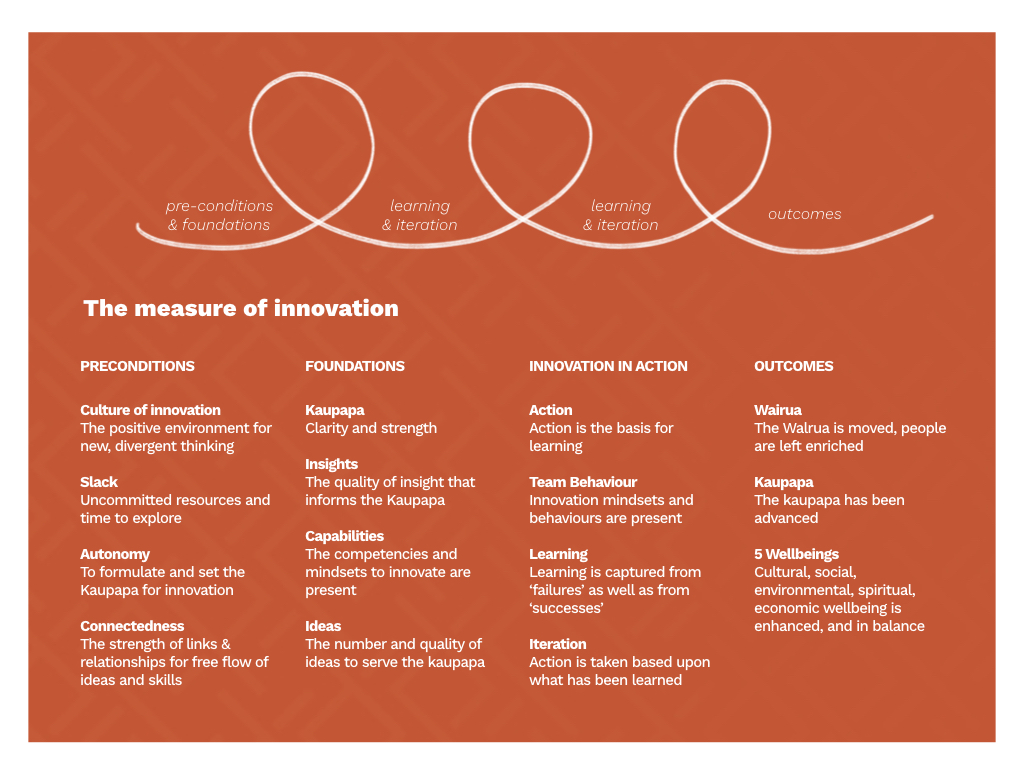

How might we measure innovation?

It might be helpful to reimagine how we understand and evaluate innovation. Income alone will not tell us how we are travelling. Below is one model for how the process, as well as the outcomes, can be measured; a move away from easy to measure, but less meaningful, metrics that encourage a success, or failure, mentality.

These measures will be considered in more context as The Future Emerging series continues. It will explore in more detail the enablers for innovation in the team or organisation, as well as in the environment in which they innovate.

In this essay we’ve considered the value of innovation and considered what it is, and how it happens. This discussion is often overlooked in favour of chasing innovation as ‘novelty’ or a ‘quick fix’. We advocate that any innovation requires a strong Kaupapa to ensure that the value and importance in innovation lies not the novelty of an idea but in what transformation is possible.

We invite you to share with Te Taumata Toi-a-Iwi what resonates, what’s missing, or any alternative perspectives that can enrich our understanding and action. We intend to collate, digest, and share the responses as the start of a dialogue on innovation in arts and culture, and how we shape the future emerging. You can do that by emailing info@tetaumatatoiaiwi.org.nz

Read the next in the series article 3: Where do we want to play, and to innovate?

For full download of Innovation in Arts and Culture in Aotearoa please click here.

This series was written in collaboration by Shona McElroy, Eynon Delamere, Jane Yonge, and Chantelle Whaiapu.

References

[1] Johar, I., (2017) Innovation Needs a Boring Revolution. Dark Matter Labs https://provocations.darkmatterlabs.org/innovation-needs-a-boring-revolution-741f884aab5f

[2] Spiller, C., (2021) Wayfinding Odyssey into the Interspace in Ngā Kete Mātauranaga. Otago University Press

[3] Castaner, X., Campos, L. (2002) The Determinants of Artistic Innovation: Bringing in the Role of Organizations. Journal of Cultural Economics. New York Vol. 26, Iss. 1, 29-52.

[4] This concept, coined by MIT’s Jason Prapas, is at the heart of how UNDP pursues innovation for development.

[5] Castaner, X., Campos, L., (2002) The Determinants of Artistic Innovation: Bringing in the Role of Organizations Journal of Cultural Economics, page 29

[6] Flemming, T. (2017) The Digital Arts and Culture Accelerator: An evaluation. NESTA

[7] Perrin, Burt. (2002). How to — and How Not to — Evaluate Innovation. Evaluation. 8. 13-28.10.1177/1358902002008001514.

[8] Cunningham, P., (2013) The Impact of Direct Support to R&D and Innovation in Firms. NESTA Accessed at: www.nesta.org.uk/wp13-03